More observations from the director:

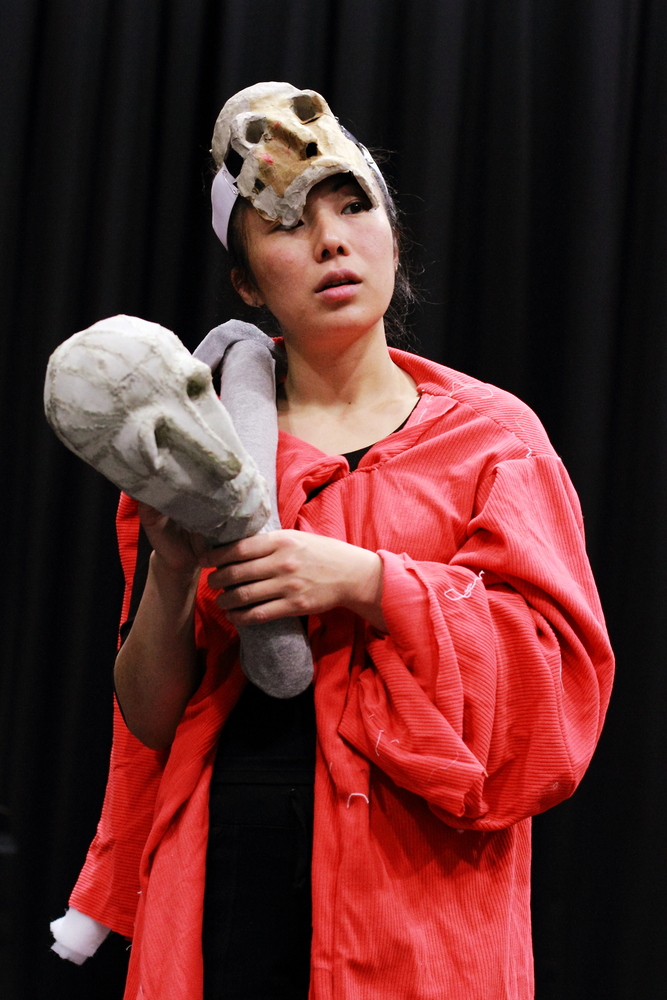

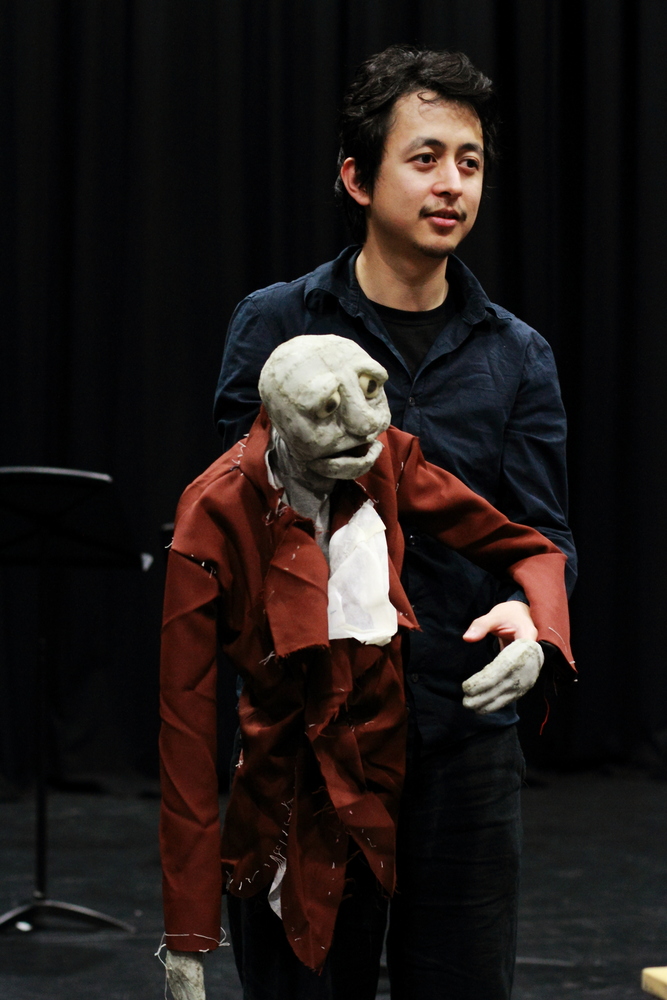

A central question we brought with us into this R&D process was about the relationship between music, movement, and puppetry. How can puppets express themselves musically, both through movement informed by music and through ‘singing’? While I am personally a huge fan of the Muppets, we want to avoid ‘Muppet-style’ singing for our puppets. This has proved a challenge, in no small part because Muppet-style movements for singing or speaking puppets has embedded itself so deeply in the movement vocabularies we tend to fall back on when puppeteering.

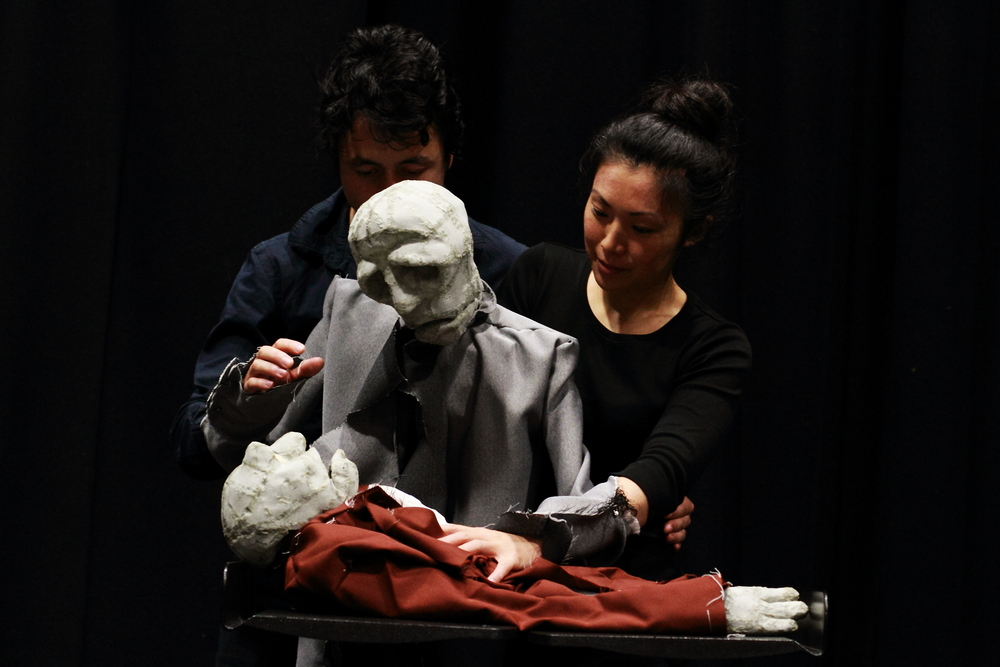

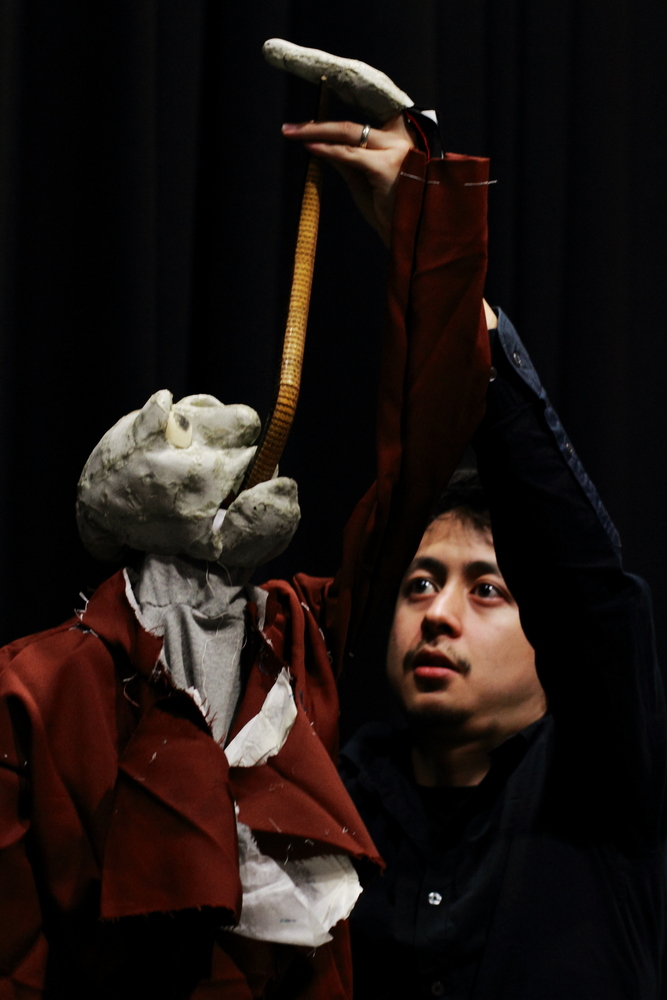

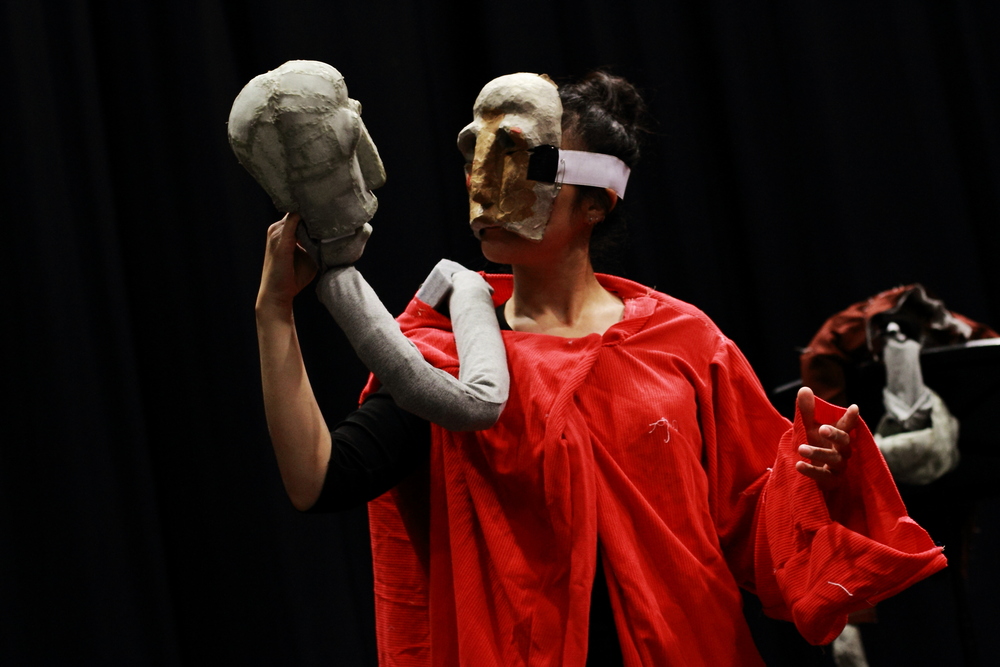

In an attempt to create a different kind of movement vocabulary for puppet singing – particularly the slower, more emotionally expressive songs in the piece – we’ve spent some time researching musical theatre performances including performances from Sweeney Todd and West Side Story. We looked closely at performers’ bodies, as our puppets must rely on bodily shifts for expression, having fairly static faces (their jaws move, but part of our aesthetic is keeping the faces rigid and finding the ranges of expression within something that is intentionally left looking like a material object rather than like an organic being).

Movement analysis of ballads in these shows has taught us several important points about the body’s relationship to emotional expression in song. First, that less is more – clear focus and restrained use of head and hand movements focuses meaning into those gestures that are used. A related point is clarity of thought – by giving a puppet a specific focus for each independent thought in a song, the meaning of the song is conveyed much more clearly. This is related to a technique that I learned from director Lisa Wolpe which she applied to Shakespearean acting, a technique she called ‘geography of thought’, in which the performer physically locates each separate thought in a monologue within the theatrical space, shifting her focus from one location to another as the thought (as expressed through the text) shifts. We played today with having our puppets do this, and it proved successful in clarifying the meaning of songs, telling the ‘story’ of the song with specificity and energy directed outward (a key point for encouraging the audience to emotionally engage with the puppet). For example, if a puppet sang the line ‘before you arrived there was only me and my sister, the others dismissed her and I’, the puppet would ‘see’ an image of her and her sister being ridiculed in the upper right corner of the audience, and direct her focus (via the puppeteer) to that image. Then as soon as the thought shifted, her visual focus would shift to another part of the theatre, where she would see a new image.

Another lesson we learned from movement analysis of musical theatre performances was the importance of physical levels of tension, particularly in the sternum. As songs build in emotion, singer/performers tend to increase the level of tension in the torso, particularly around the emotionally-expressive centre of the sternum. We initially weren’t sure whether this would translate to puppet physicality, but found that – at least with the puppets in this show – it does: they can increase tension in their torsos, and expand or collapse their sternums, in order to convey particular types of emotional engagement.

We’re looking forward to more discoveries around this theme of movement/music/puppetry, and also to hearing Ferment audience feedback on how they found the puppets’ singing of their more emotionally-charged songs!