by Professor David M. Turner, Swansea University

The term ‘freak show’ evokes past attitudes to biological diversity very different to our own. The exhibition of human and animal anomalies has become synonymous with exploitation, cruelty and, given the increasing popularity during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of shows involving ‘exotic’ non-European human beings, racism. But human exhibition took a variety of forms in the past, and had a variety of motives. Indeed, the modern notion of the ‘freak show’ as a travelling form of entertainment involving several performers working for a manager or showman was an invention of the mid-nineteenth century, thanks to entrepreneurs such as P. T. Barnum in the United States, and Tom Norman in England.

The exhibition of ‘monsters’ and other human and animal curiosities became popular in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. During this period pamphlets detailing ‘monstrous births’ were popular. These phenomena were sometimes interpreted as portents – sending messages of divine displeasure – or as medical curiosities. The development of learned societies such as the Académie des Sciences in Paris and the Royal Society in London from the late seventeenth century fostered growing scientific interest in the wonders of nature and a desire to use them to understand better the natural processes of human development. This learned interest in monstrosity contrasted with popular curiosity in human aberrance, catered for by the display of conjoined twins, people of restricted or exceptional growth, or those born without limbs in fairs and taverns. Human exhibition was not confined to physical ‘deformity’. Popular performers in seventeenth-century England included the ‘posture master’ Joseph Clark – a contortionist – and Nicholas Wood, the ‘great eater of Kent’, who like Tarrare was famed for his remarkable powers of digestion.

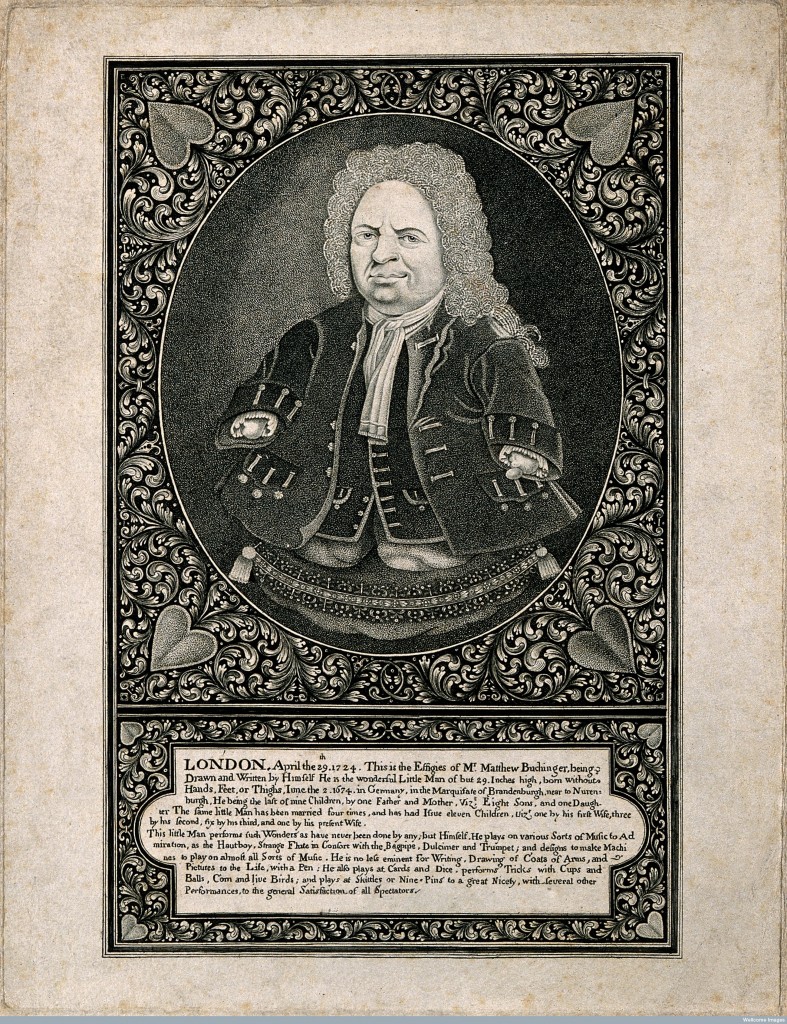

During the eighteenth century some performers gained considerable fame, helped by the growth of the newspapers and the use of advertising for performances. Although the social elite increasingly distanced themselves from tavern and fairground entertainments, some performers aimed their shows at more genteel audiences. Matthew Buchinger (1674-1739), the ‘little man of Nuremburg’, born without arms or legs, exhibited himself before royalty and aristocracy across Europe before coming to England in 1716. He deliberately courted an elite audience, promising private performances in the homes of ‘ladies and gentlemen’ and seeking their patronage for artistic work such as drawing coats of arms and family trees. Russian emperor Peter the Great collected examples of human diversity and exhibited them at his court. Many performers advertised their exceptional skills and refined manners. The appeal of human exhibition as an entertainment often depended on the contrast between the performer’s ‘normal’ attributes (such as their good manners or settled domestic life) and their remarkable appearance or talents. Some entertainers such as Buchinger made a good living from displaying themselves and human exhibition may have been a preferred choice of making a living for some people with disabilities for whom other options may have been limited. However, their success depended on their novelty, which meant that they often had to travel and seek out new audiences and patrons.

Matthias Buchinger, a phocomelic. Engraving after a self portrait. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org

When concerns were raised about human exhibition in the eighteenth century, they primarily focussed on the potential for disorder associated with large plebeian gatherings at fairs or taverns rather than the exploitation of performers. However, in 1810 the case of Sartjie Baartman, the so-called ‘Hottentot Venus’, became a legal cause célèbre in London when a lawsuit was brought against her ‘keepers’ for exhibiting her without her consent. Baartman was born to a Khoisan family in the East Cape of South Africa in 1789 and had been persuaded to travel to Britain to exhibit herself to audiences fascinated by her distinctive anatomical features (particularly her large buttocks). However, following Britain’s ending of the slave trade in 1807 the abolitionist group, the Africa Society, brought a case challenging her exhibition. In her own evidence, Baartman claimed that she exhibited herself freely and claimed the right to earn a living this way. However, her case revealed the vague terms on which human exhibits were employed by their promoters. She moved to Paris in 1814 where she became the subject of interest of doctors and naturalists, while continuing to exhibit herself to popular audiences. After her death in 1815 she was dissected.

![L0048076 Hottentot Venus Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Small poster advertising the exhibition of the Hottentot Venus, a black woman (presumably Sarah Baartman, 1789-1815) from "the most southern parts of Africa" in what was probably seen in the less enlightened days of 1810 as a travelling "freak show". People from various racial backgrounds toured these show circuits, dressed in traditional costume, entertaining people who had never seen other than local, white people before. Sarah Baartman was extensivley toured, exhibited and subsequently dissected upon her death in 1815. Just arrived from London, and, by permission, will be exhibited here for a few days at Mr. James's Sale Rooms, corner of Lord-street : that most wonderful phenomenom of nature, the Hottentot Venus : the only one ever exhibited in Europe. 1810 Just arrived from London, and, by permission, will be exhibited here for a few days at Mr. James's Sale Rooms, corner of Lord-street : Published: [1810]](https://egjl2015.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2015/08/L0048076-724x1024.jpg)

Small poster advertising the exhibition of the Hottentot Venus Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org

Sartjie Baartman moved between the popular world of entertainment and learned medical interest – just as Tarrare did. Interest in the ‘freak’ was never simply a matter of raucous entertainment or cruel exploitation of the ‘unfortunate’ (although may be part of the story). The taste for ‘freaks’ in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was part of a broader interest in the limits of the human, in classifying and explaining the variety of nature. The world of the ‘freak’ crossed boundaries between science and showmanship, between autonomy and exploitation and between the elite and the popular. ‘Freaks’ were exhibited for their difference, but taught people about what it meant to be human.