by Dr Alan Bates, Honorary Senior Lecturer in Pathology, University College London

When Baron Percy opened the body of Tarrare, he was performing an autopsy, a procedure designed to reveal what the Italian anatomist Giovanni Morgagni had called, some thirty years earlier, ‘the seats and causes of disease.’ The search for post-mortem physical changes that could show what illnesses a patient had suffered during life was to develop into the new science of anatomical pathology, and Morgagni’s phrase was incorporated into the motto of the London College of Pathologists almost two hundred years later. We may take it for granted that a post-mortem examination can discover the cause of death, but in Percy’s time, the idea that the appearance of particular organs and tissues could be used to diagnose disease was novel. There were no professional pathologists to make post-mortem examinations; surgeons had to do it for themselves, and it helped if, like Percy, they were skilled anatomists. The study of disease in terms of the pathology of tissues and organs helped to dispel the time-honoured concept of four bodily humors that got out of balance when a person was ill. From a modern perspective, however, it is far from clear that Tarrare’s depraved appetite was due to disease in a particular organ: an abnormal constitution, or mental illness, have just as well have been responsible, in which case Percy was seeking something that he could never have found.

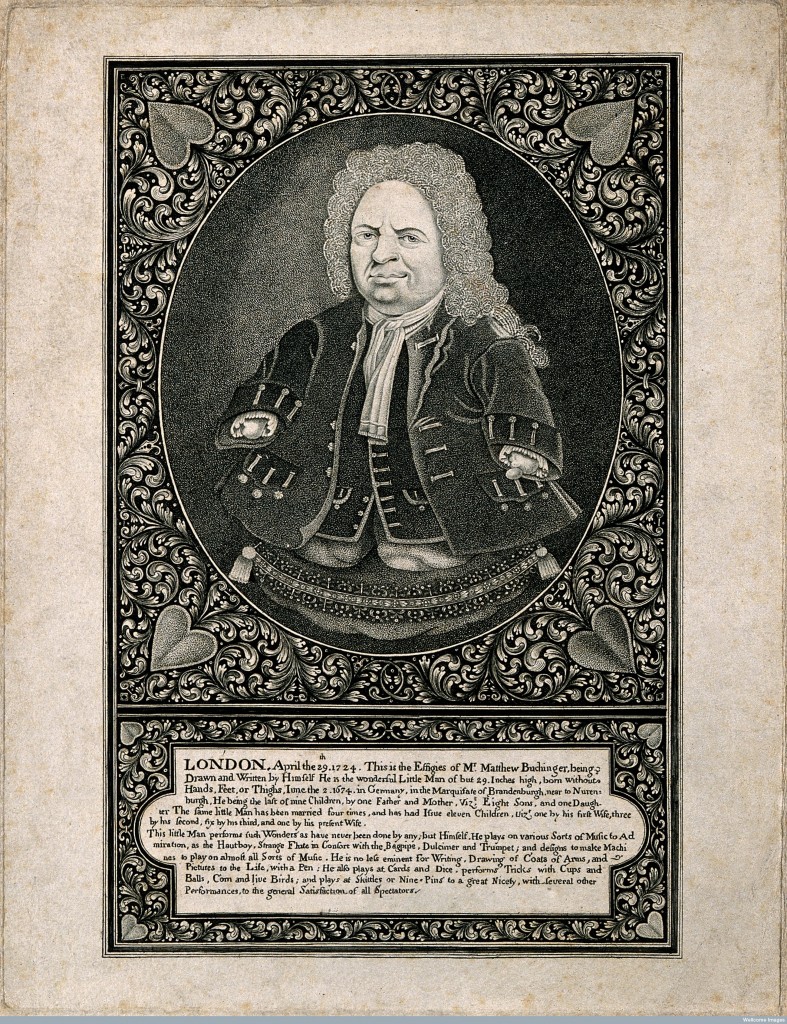

Many people think that the autopsy was developed by opening up the bodies of the unwilling poor, just as anatomists relied on body-snatchers to supply corpses, and was hampered by opposition from the Catholic Church. In fact, autopsies were fashionable among the well to do, who saw them as intellectually enlightened, and were performed on popes and princes. The unclaimed bodies of patients who died in hospital did provide an important resource for study, and were used without the patient’s or relatives’ consent, but this was relatively uncontroversial. It must be borne in mind that in the eighteenth century there was nothing akin to the modern notion of informed consent in medicine; the question of who owns a body was raised, but the correct legal answer was (and still is) ‘no-one,’ for bodies are not property and cannot be stolen.

The shift in emphasis in late-eighteenth century medicine from the whole body to specific organs and tissues, sometimes studied at microscopic level, was not uniformly welcomed. While there were many enthusiasts for the modern, scientific medicine of the clinic and the laboratory, some patients bemoaned the disappearance of the ‘holistic’ doctor with a kindly bedside manner, who saw them as a whole person and not a collection of cells and tissues. The two approaches are not incompatible, and it can be helpful to consider illness from these different perspectives. Our understanding of Tarrare’s troubles comes partly from Percy’s autopsy findings but also from reconstructions of his life through which we can imagine his experiences as a patient. Suffering, seeking a cure and feeling isolated or even freakish remain part of a patient’s journey despite medicine’s scientific advances.

We are entitled to ask, however, what was wrong with Tarrare from a modern medical point of view, and whether present-day treatments could have helped him. Tarrare had a huge appetite, drank water copiously, and was ‘apathetic.’ His body was reported to have had an unusual odour, especially after eating. Despite his excessive consumption, he never gained weight, and sweated profusely. Did he suffer from a damaged amygdala, part of the brain that controls appetite? Perhaps he had diabetes – a disease unknown at the time – which when untreated can produce all of these symptoms. We cannot know whether Percy, given access to a modern pathology laboratory, could ever have found what he was looking for, or whether Tarrare’s condition was truly something unique to him.

![L0048076 Hottentot Venus Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Small poster advertising the exhibition of the Hottentot Venus, a black woman (presumably Sarah Baartman, 1789-1815) from "the most southern parts of Africa" in what was probably seen in the less enlightened days of 1810 as a travelling "freak show". People from various racial backgrounds toured these show circuits, dressed in traditional costume, entertaining people who had never seen other than local, white people before. Sarah Baartman was extensivley toured, exhibited and subsequently dissected upon her death in 1815. Just arrived from London, and, by permission, will be exhibited here for a few days at Mr. James's Sale Rooms, corner of Lord-street : that most wonderful phenomenom of nature, the Hottentot Venus : the only one ever exhibited in Europe. 1810 Just arrived from London, and, by permission, will be exhibited here for a few days at Mr. James's Sale Rooms, corner of Lord-street : Published: [1810]](https://egjl2015.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2015/08/L0048076-724x1024.jpg)